By Monalisa Salib, Deputy Chief of Party for USAID Learns, a USAID/Vietnam support mechanism, implemented by Social Impact, Inc.

This 2nd blog in our series summarizes key messages from recent Theory of Change (ToC) training for USAID/Vietnam staff. Special thanks to Lane Pollack and Shannon Griswold from USAID’s Bureau for Policy, Planning & Learning (PPL) and David Fox from Asia Bureau for their collaboration in designing and delivering this training. See the first blog on what it means to have a strong theory of change.

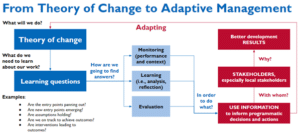

Sometimes we forget after design or start-up that the theory of change (ToC) is just what the name implies – a theory. We might put it up on a shelf and think, “That was great – now let’s implement!” But what happens when our theory faces reality? There’s a chance it may not pan out. We may have been wrong, or things could have changed in the context. The entry points we thought existed may have fizzled. The assumptions we were once confident about may not be holding. And the interventions we thought would get us to our outcomes don’t seem to be moving the needle. When we are humble, we can admit that these are all possible and recognize that the ToC is something that we need to monitor, reflect on, and adjust as needed. This is why we need to bring the ToC into our management practices throughout implementation.

In the training, we introduced three management practices and one principle in practice described below to provide concrete options for how the theory of change can be used, revisited, and potentially adjusted during implementation. See the first blog on strong ToCs if you haven’t already! You can always revisit your ToC to make it stronger and more management-useful.

Management practice #1: Learning with purpose

When we have a strong, context-driven theory of change with clear entry points, outcomes, assumptions, and interventions, we set ourselves up for learning with a purpose during implementation. Learning with purpose means defining key learning questions specific to our ToC and focusing monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) activities on answering them.

In the training, we had participants go through an exercise based on the ToC example found here. One of the entry points identified in that fictionalized ToC (based in Marshovia) was that a neighboring country (known as San Lola) had experimented with Alternative Rehabilitation Centers for youth as a way to reduce the chances of previously incarcerated youth returning to jail (recidivism). San Lola saw great success with that model, including lower incarceration costs and reduced recidivism rates. Based on this, one of the learning questions posed by the implementing partner in the Activity Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning Plan (AMELP) was: What are the most important elements of the ARC model that worked in San Lola that need to be replicated or contextualized in Marshovia?

Participants were asked to consider: Is this a strong learning question? How will it help improve implementation? In determining whether this question would enable the team to learn with purpose, participants considered:

- Who needs to know the answer?

- What specific information do they need?

- In order to what? What decision or action will take based on this information?

Based on this example, participants determined this was a strong learning question that would enable the implementation team to scale San Lola’s model in Marshovia and operationalize a key entry point identified in the ToC.

We find answers to learning questions – like the one in the example – by implementing certain MEL activities. In this case, it may be an assessment of the San Lola model along with key informant interviews in Marshovia to understand how to apply aspects of the model locally. What we learn should inform our management decisions and interventions – in this case, how do we bring the best of the San Lola model to Marshovia? What adjustments will we make to account for contextual differences?

Management practice #2: Monitoring meaningfully

What you monitor should be driven by your ToC and align with the four elements (outcomes, entry points, interventions, and assumptions – see blog #1). This requires both effective performance monitoring (to track outcomes and outputs as a result of interventions)[1] and context monitoring (to track changes in context, entry points, and assumptions).

Through performance monitoring and context monitoring practices, teams can answer the following learning questions:

- Are the entry points identified panning out? Have new entry points emerged?

- Are the assumptions holding?

- Are we on track to achieve the outcomes[2] we identified? Are our interventions (outputs) leading to outcomes?

Outlining the team’s plan for monitoring meaningfully is done in the AMELP. See this AMELP template that supports meaningful monitoring from USAID/Vietnam.

Management practice #3: Pause and reflect to plan

Pause & reflect refers to an intentional practice of “taking time to think critically about ongoing activities and processes and to plan for the best way forward” (see the CLA toolkit for more on pause & reflect). As we implement programs, it is critical to regularly check in on your ToC, particularly ahead of annual work planning, to make adjustments for the next year based on learning.

While the practice of pausing and reflecting on specific interventions is gaining more popularity in international development via approaches like after action reviews, we also need to take a bigger, strategic step back and connect pause and reflect discussions to the ToC. Based on what we learn through the management practices above, the ultimate question is: does the theory of change still hold? What needs to be modified based on experience and learning? It is critical to do this before annual work planning, as the work plan is the guide for implementing the theory of change and achieving identified outcomes. For more on theory of change reviews, see this blog post.

Principle in Practice

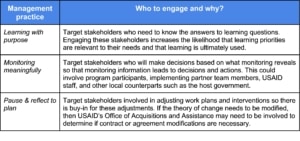

We highlighted a key principle that applies across each practice: engaging stakeholders, particularly local stakeholders, as documented in the table below.

After sharing these management practices and the principle in practice with the group, we asked for their proposed actions to bring these approaches to life in their work. Here are some ideas they shared that might inspire you to strengthen your ToC or use it more intentionally during implementation:

- Review our activity’s ToC to make sure it is strong and sets us up for better implementation and integration of the above management practices

- Review our Activity Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning Plan (AMELP) to make sure we are integrating learning questions that enable us to track elements of the ToC

- Track outcomes in a regular way throughout implementation to ensure we are on track for success (or need to make adjustments)

- Incorporate a ToC review and update ahead of our next work plan cycle

- Review our activity’s ToC with local stakeholders for their inputs

For more on developing or strengthening ToC, see this related post and ToC workbook that takes users through a step-by-step process.

Cover Photo Credit: DNY59, Getty Images

[1] See this blog for more on meaningful performance monitoring.

[2] Outcomes are significant changes in the “conditions of people, systems, or institutions that indicate progress or lack of progress” (USAID ADS 201). Outputs, on the other hand, count things; the number of people trained is a common example.