Supporting locally-led monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) requires shifting power and ownership from historically dominant institutions to marginalized actors. Real-world examples are crucial to guide this change but are also rare given the persistence of this challenge.

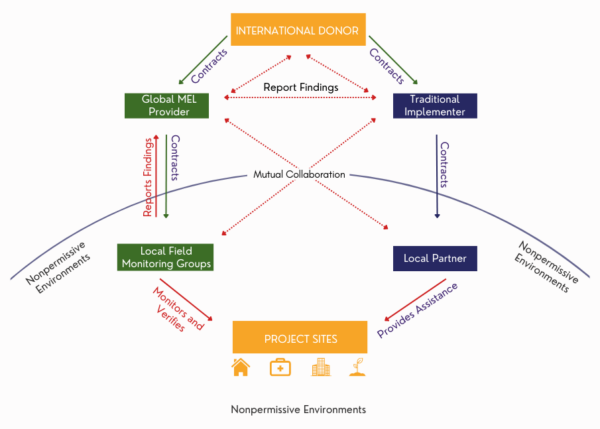

One such example includes the practice of contracting third parties to verify donor-funded activities in non-permissive environments. Here, local actors play key roles ensuring aid reaches its intended beneficiaries. Both global and local organizations conduct third-party monitoring (TPM), yet even when international entities are involved, those groups verifying facts on the ground are typically legally organized and based locally where they operate (see “Local Field Monitoring Groups” in the graphic below).

The experiences of TPM organizations offer instructive examples on how locally led MEL can strengthen mutual accountability and learning, collaboration, innovation, and risk management for supporting locally led MEL.

• Reinforcing mutual accountability and learning. Because third-party monitors act as eyes and ears for donor staff unable to visit project sites, their work can be perceived by implementing partners (IPs) as oversight rather than learning potentially setting up a confrontational rather than collaborative relationship. Though TPM does play an important role in preventing fraud, waste, and abuse, successful field monitors link data verification to learning by delivering findings rapidly for course corrections and with sufficient depth to improve outcomes. In doing so, TPM applies the principles of mutual accountability and mutual learning from USAID’s Local Capacity Development Policy. USAID and local field monitors have already begun working in partnership, “collaboratively measuring change and jointly analyzing and interpreting data, to prioritizing areas for program adaptation.”1 This provides examples for the Agency and others to study and replicate in other environments.

• Leading external collaboration. Third-party monitoring organizations excel at coordinating with a range of stakeholders to identify project sites, understand the intended results of this assistance, assess its actual effects, and communicate out these findings and their associated recommendations. They do this with international funders, traditional international organizations and the local entities in non-permissive environments contracting with them, and beneficiaries at the sites. This consistent and systematic external collaboration represents a locally led success for USAID’s collaborating, learning, and adapting (CLA) approach and demonstrates the spectrum of global and local actors with whom those supporting localization must engage to have similar impact.

• Fostering local innovation. While innovation is commonly associated with new technology, it also refers to any new method or idea. Local organizations and actors apply both to deliver TPM in insecure environments. Before smartphones existed, organizations equipped field monitors with watches with hidden cameras to help complete verifications quicker and with less personal risk than using an unconcealed camera. More often third-party monitors generate new ideas to overcome access restrictions like using crowd-sourced information in Mali or establishing call centers to converse in distinct regional dialects in Somalia. Ideas like these demonstrate the bottom-up, dynamic innovation that can come from supporting locally-led MEL.

• Demonstrating how locally-led development mitigates risks. Historically dominant institutions have at times suggested that shifting power and decision-making to local organizations is a higher risk than using traditional implementing partners because of their lower capacity. Yet, TPM challenges this perception by demonstrating an entire category of development work where funders have successfully shifted power to local field monitors. It should be acknowledged that this shift in ownership involves transferring significant risk to field monitors, who may be subjected to physical danger or even death while verifying development activities in their communitie.. While the success of locally-led development in TPM in no way lessens this transfer of risk, it also underscores the moral imperative of shifting power and ownership to local MEL actors who are best placed to make decisions about the risks and benefits of their work.

Third-party monitors play key roles verifying IP reporting and informing decision making. One study found that 56 percent of aid agencies working in insecure contexts reported being unsatisfied with IP’s own monitoring and evaluation,2 signaling TPM will be part of development and humanitarian assistance for the foreseeable future. This example of successful locally-led MEL can help guide those seeking to change current systems and incentives to promote greater participation and leadership by local MEL actors.

————————

Authors:

Chris Thompson leads the technical implementation and oversight of monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) contracts for Social Impact around the world. His over 15 years of experience includes long-term, field-based senior management and technical positions in Indonesia, Liberia, the West Bank, and Afghanistan where he put into practice pioneering evaluation approaches and award-winning collaboration, learning, and adapting (CLA) techniques.

Jenn Mandel has more than 25 years of experience in monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) for international development programs. In her almost seven years at Social Impact, she has served in both technical and management leadership roles, including supporting long-term, field-based project offices. In these capacities she has supported technical implementation and provided technical support to and oversight of all aspects of MEL task implementation. She has worked in the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South and Southeast Asia, including non-permissive and challenging environments such as Haiti, Pakistan, and Mali.

Photo by: Blue Planet Studio, Adobe Stock