This blog is part one of a six-part series on localization. Localization is a power-shifting process, where power is shifted to local actors to address development challenges. Over this series, Social Impact unpacks its own experiences on localization to shed light on our process and provide lessons learned for our funders, peers, and partners.

As USAID and its implementing partners increasingly prioritize localization, it is important to take a step back to understand what this means. Localization can be considered locally-led development, participatory development, local ownership, or other similar terms. As an international development community, we need to know what knowledge already exists about localization among our staff and where the gaps are that need to be addressed. To answer these questions for ourselves, Social Impact (SI) conducted an internal stocktaking of localization knowledge, and we are sharing that process here in the hopes that your organization can learn from our experiences and that, together, we can be more effective localization partners as we work to improve the lives of the people we serve.

Our Process

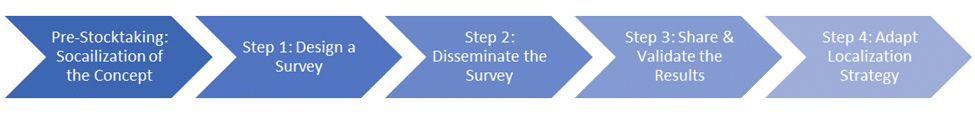

Pre-Stocktaking: Socialization of Localization

Before the internal stocktaking, SI’s core localization team socialized the concept of localization by defining the term and why it matters to us. We then listed our next steps, which included conducting an internal localization stocktaking. This “pre” step is important to demystify the term “localization” and to ensure no one is getting lost in the jargon. This prevents us from losing out on engagement because people do not connect the term being used with what they are doing.

Tip: Provide an initial definition of localization but offer multiple terms to help people connect what you mean with what they are doing.

Step 1: Design a Survey

Our next step was to define what information we wanted to know from the stocktaking. We bucketed our questions into three categories: (1) How do staff perceive localization? (2) How do staff define localization? and (3) What are our experiences and examples of localization? We then defined who should be taking this survey; opening it up to all our employees, both in the U.S. home office and in our international project offices. The survey mainly targeted questions around USAID-localization experiences, although USAID experience was not required. Based on the survey flow and an individual’s experience, completing the survey could take as little as 5 or as long as 30 minutes (if the respondent was very detailed)!

The survey incorporated links to our pre-stocktaking socialization documents, definitions, and graphics to help the respondents. They were also given open-ended response options to capture more details. You can see our full survey here.

Tip: Keep the survey short and to the point.

Step 2: Disseminate the Survey

The survey was disseminated to all staff via email, with instructions on what to do and a deadline for completion. Our team did not expect all staff to engage, as the survey itself is quite specific to those interested or experienced in localization efforts. Keeping in mind that it is notoriously challenging to achieve high response rates for voluntary employee-engagement surveys, our survey participation was low, especially from our project offices. If your organization decides to conduct a stocktaking, more specific engagement with project offices may be required. Our Vietnam project office had the highest response rate out of all the offices because their Chief of Party also leads the localization initiative.

Tip: Send reminder emails (but not too many). Task division leads, chiefs of party, or supervisors to encourage participation.

Step 3: Share and Validate the Results

After the survey ended, our localization intern, with support from the localization team, analyzed the results. A summary of the findings was presented at a cross-divisional meeting which was also used as an opportunity to learn and generate more knowledge about localization. After the presentation, we broke out into four virtual groups. Each group focused on one of the following questions: (1) what is considered localization? (2) should we advocate for localization with donors? what does advocacy look like? (3) what is SI’s value-add in the localization conversation? and (4) what barriers and opportunities could we tackle internally? Each breakout room had a facilitator who guided the conversation and recorded responses.

Tip: Participatory presentations are a great way to capture additional knowledge about your organization’s localization experience and understanding. Use the information gathered from breakout rooms as additional data for the stocktaking.

Step 4: Adapt your Organization’s Localization Approach Based on Inputs

After the meeting, we had three rich sources of information: (1) the pre-stocktaking localization concepts and early work plan, (2) the survey results, and (3) the breakout room feedback. Realizing that we needed more feedback from our international project offices, we added another input—a brainstorming session, particularly among cooperating country staff. We asked two simple questions: (1) what are you already offering to USAID to advance localization? and (2) what more do you want to be offering?

All the gathered information was analyzed and integrated into a localization menu of services that our organization could provide to clients. We also created localization “smart rules,” which are simple practices SI staff can incorporate into their day-to-day work with the intention of improving and increasing localization. We are currently working on socializing the menu of services and smart rules internally for adoption across our organization. Check back soon to learn more about our smart rules in an upcoming blog post!

Tip: Keep all documents utilization-focused. Use simple tables, bulleted lists, memo-styles, and other formats of concise depictions of information.

By gathering employee-informed perspectives and backgrounds, SI is better able to draw on our experiences and identify the areas where we are strong and as well as where need to learn and and expand our capabilities. We can use this information to make informed decisions about where to place our resources, where to build up skills, and what we should do next to promote localization. While the stocktaking was an important step towards localization, it is only a step—this is just the beginning of a concerted and important effort to shift power where it belongs: with local organizations and the populations they serve.

______

Brooke Hill co-leads Social Impact’s Equity Incubator a learn-do initiative that works at the intersection of data, learning, equity, and inclusion. She serves as the technical lead of BRIDGE and Project Director of the Managing Agency Priorities mechanism which supports equity, inclusion, and organizational development within USAID. She is a Senior Program Manager in SI’s Strategy, Performance, and Learning division.