What Are Key Issue Narratives?

Key Issue Narratives (KINs) are an underutilized resource for learning and engagement across USAID. As part of the required annual Operational Plan (OP) and Performance Plan and Report (PPR) reporting process, KINs consist of narratives submitted by USAID operating units (OUs) on 50 or so cross-cutting topics such as biodiversity, gender, and digital technology.

Given the amount of effort that goes into drafting these narratives, they deserve to be pored over, analyzed, and utilized. USAID’s Digital Strategy team members have tried to do just that in our developmental evaluation—leverage KINs for learning and decision-making!

Why Are Key Issue Narratives So Valuable?

KINs have the potential to improve learning and collaboration across USAID for several reasons:

- KINs provide USAID staff with visibility into programming across the entire Agency in many cross-cutting areas of interest. Given USAID’s decentralized structure, it’s difficult to obtain this sort of visibility, making KINs especially valuable.

- KINs have the potential to promote engagement, especially between USAID/Washington and Missions but also from Mission to Mission. After reading KINs, staff have reached out to learn more about programs or share resources.

- KINs can provide data contributing to monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) indicators and can help OUs track performance, especially of Agency-wide priorities, strategies, or policies.

- KINs provide deep information about enabling and constraining conditions, program implementation, and most importantly development outcomes, all of which are difficult to learn from quantitative data. KINs tell the story of our successes and challenges.

How Have We Analyzed the Narratives?

As part of a developmental evaluation of USAID’s Digital Strategy, we have tried to take full advantage of the treasure trove of information in KINs by conducting analyses of the fiscal year (FY) 2020 and FY2021 KINs related to digital development. We selected three sets of KINs that were most likely to describe digital development programming and coded them to identify patterns and trends:

- Digital Technology Key Issue Narratives

- Science & Technology Key Issue Narratives

- Cybersecurity Key Issue Narratives

Using a qualitative database analysis, we read through these three sets of narratives carefully, categorizing them according to sector, region, and specific areas within digital development. The codes used in the analysis were chosen in a participatory fashion based on input from staff members in the USAID Innovation, Technology, and Research (ITR) Hub’s Technology Division (previously the Center for Digital Development in the U.S. Global Development Lab) in a Connect & Reflect session and from subsequent conversations with Digital Strategy initiative leads as well as others.

How Were the Findings Put to Use?

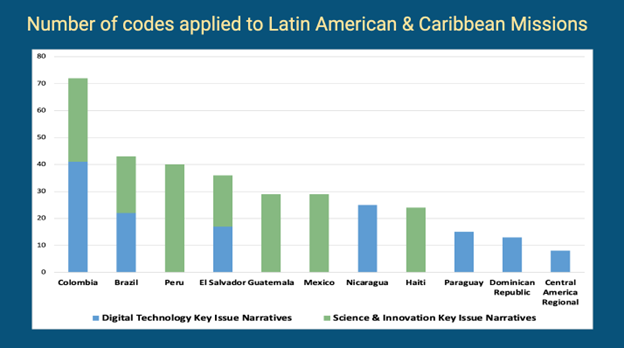

Many insights emerged from this analysis. To take just one example, we learned that OUs were describing programs involving digital development in both the Digital Technology and the Science & Innovation sets of KINs (see Figure 1). We shared these findings with MEL staff from USAID Missions in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region, which prompted fruitful discussions about what sorts of digital development programs were being implemented in which countries, and how future submissions of KINs could provide even more details.

Figure 1. Number of codes relevant to digital development in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region’s FY20 Digital Technology (blue) and Science & Innovation (green) Key Issue Narratives. Missions not included in the chart did not submit these narratives in FY20.

Perhaps even more valuable than the overviews and trends discerned from the FY20 and FY21 KINs were the excerpts that we were able to provide in response to internal Agency briefers, memos, or other requests. Because staff members had been involved in the identification of codes, once the analysis was completed, a number of them asked to see compilations of KINs excerpts related to specific topics, sectors, or regions, such as the following:

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning

- Economic growth

- Global (public) digital goods

- Humanitarian assistance

- Resilience

- Digital payments and digital financial services

- Digital literacy

- Countries and regions, including Indonesia, Philippines, Ukraine, Africa, and the Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras).

These compilations of narrative excerpts informed the creation of several bureaus’ Digital Action Plans or other strategic undertakings. In one case, for example, the Digital Strategy Team was asked to compile information within a very short time on how USAID provided digital development programming to Northern Triangle countries—El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—as part of the Office of the Vice President’s focus on that region. Without the KINs, we would not have been able to compile and learn about our work in this strategically important area in a short turn around. Drawing on the KINs, we were able to report, for example, on partnerships between USAID, Microsoft, and the Government of Honduras to provide greater connectivity in rural areas. The KINs also allowed us to share data that demonstrated improved health outcomes from digital development projects focusing on health informatics. These and other examples demonstrated digital activities beyond information provided in Global Acquisition and Assistance System (GLAAS) tags or budget lines.

Limitations and Suggestions

While the KINs constitute an admittedly partial dataset and should not therefore be interpreted as providing definitive evidence about the full scope of USAID’s programming in any given area, they nevertheless offer valuable insights that can inform Agency activities and enhance engagement within and between Missions and USAID/Washington. For staff interested in learning from KINs in their own sectors or areas of expertise, here are two suggestions for how to conduct the analysis:

- Obtain input on codes and other aspects of the analysis from a wide set of potential users of the findings, as research has shown that people are more likely to apply evidence that they were involved in developing. Such sessions also help to publicize the analysis and eventual findings.

- Once the analysis is complete, or perhaps even while the analysis is still underway, share the findings with multiple audiences. Request feedback on the analysis and encourage audience members to consider ways they could apply the findings.

——————-

Contributing authors:

Laura Ahearn is a Technical Director with Social Impact. She is currently conducting a developmental evaluation of the implementation of USAID’s Digital Strategy. Previously, she was part of the LEARN contract and worked on the DRG Learning Agenda, the Program Cycle Learning Agenda, and the Self-Reliance Learning Agenda. She has a Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Michigan and was a tenured faculty member at Rutgers University.

Eric Keys is the Digital Strategy Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning Specialist. Prior to joining USAID he carried out various strategic and evaluation duties at the Department of State, Department of Defense, the National Science Foundation and as an applied researcher in Africa and Latin America on agricultural, climate change, and natural resource management interactions. He holds a PhD, in Geography from Clark University and was a faculty member at the University of Florida and Arizona State University.

Photo by: Anna Nekrashevich