A recent study finds that female labor force participation in India dropped by nearly 20 million between 2004–05 and 2011–12. This precarious drop is a matter of significant concern, particularly when India experienced an impressive annual GDP growth rate of around 8.6 percent with a low annual population growth rate of 1.74 percent. However, the findings are not all bad news. The study suggests that some of the reasons for the drop include improved access to higher education and increased stability in family income. To increase female labor participation, the authors recommend policies that promote women in the workforce and invest in economic sectors in rural areas that are attractive to female employees.

Researchers from the World Bank Group, Social Impact (Washington DC) and Center for Development Studies (India) jointly conducted the study.

Background

Female labor force participation rate (FLFPR) in India was never impressive. Within the region, India’s FLFPR is lower than Bangladesh (57 percent), Nepal (80 percent), and Sri Lanka (35 percent). The International Labor Organization (ILO) (2013) places India’s FLFPR at rank 121 out of 131 countries, one of the lowest in the world. For a long time, it has been argued that strict social norms, gender relations and daughterly guilt play a crucial role for Indian women in abstaining from joining the labor force. While these long-held notions cannot be ignored entirely, the question is what changed so dramatically within such a short period of time that led to this precarious drop?

Findings

The study suggests that there are three main reasons:

- Improved access to higher education among young adults.

- Higher competition for white collar jobs that mostly catered to women with college education, and

- Increased stability in family income.

Increase in access to education

The study shows that while the drop occurred across all socio-economic, age, and educational groups and geographic locations, a rise in access to education was the primary reason for the decline in labor force among young women, particularly in rural areas. As high as 53 percent of this drop occurred in rural areas, and among those ages 15 to 24 years.

To establish their point, the authors used combined participation rate (CPR) which is simply the sum of labor force participation rate and attendance rate among females within same age group. Based on this index, the study shows that rural CPR for the age group of 15 to 24 years increased from 52.7 percent in 1993-94 to 55.5 percent during 2011-12 (Table 8, pp 13).

Interestingly, the 19.3 percent decline in FLFPR for this age group was more than compensated by a gain of 22.1 percent in educational participation during this period. The study shows the similar phenomenon for urban young females as well. Looking through this lens, it may be a welcome change because more and more rural young females are opting out of the labor market for higher education which provides opportunities for better future income.

While the increase in educational attendance explains the drop among young women, it does not explain the entire story.

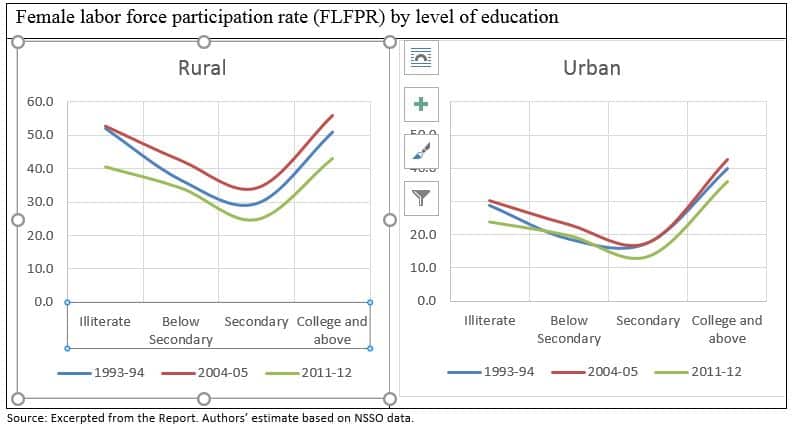

The relationship with level of education

The study delves deeper and finds a U-shaped relationship between levels of educational attainment and female labor force participation. This relationship indicates that labor force participation among women with mid-level education (viz. below Secondary, Secondary and Higher Secondary) is relatively lower as compared to women with no education and women with college degrees and above. According to the authors, it may be due to the fact that increasing demand for white collar jobs among females with higher education far exceeds the supply. Moreover, due to excess demand, the jobs mostly cater to women with college degrees. As a result, females with mid-level education are falling behind with no interest to go back to relatively lower skilled jobs.

Increasing family income stability

Finally, the study shows that the female labor force participation decision is inversely related to stability in family income. By decomposing relative shares of various groups of indicators, the study shows that the increasing share of regular wage earners and declining share of casual labor in the composition of family labor supply, has led female family members to choose dropping out of, rather than joining, the labor force (Table 14, pp). Estimation of the relative contributions of employment composition in a family explains more than 60 percent of the variation in FLFP decisions— both spatially and inter-temporally. While this phenomenon can partially support the view of social norms, some argue that with higher family income, women stay home.

Recommendations

As the authors recommend, increasing women’s access to education and skills, which is important in its own right, will not necessarily lead to a rise in FLFP. Policies should center on promoting the acceptability of female employment and investing in economic sectors in rural areas that are more attractive in terms of female employment.

See the full report here.