By Monalisa Salib, Deputy Chief of Party for USAID Learns, a USAID/Vietnam support mechanism, implemented by Social Impact, Inc.

This is the question we were recently asked by a USAID staff member responsible for managing awards. I was shocked to realize we didn’t have a straightforward answer to this simple, yet fundamental question. We are sharing our response here in the hopes that it helps others use the information gathered through performance monitoring in order to manage adaptively.

Credit: Jessica Ziegler

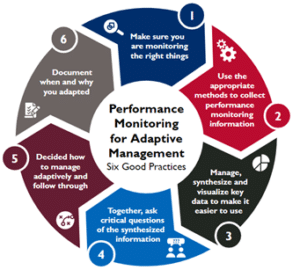

So first, what is performance monitoring and what is adaptive management? Performance monitoring here refers to the collection and use of information about a program’s outputs and outcomes to determine if the program is on track to achieve development results. Performance monitoring can be both quantitative and qualitative.[1] Adaptive management refers to the systematic and intentional practice of adjusting implementation in response to new information (like performance monitoring information!).[2]

In reality, we often find ourselves using performance monitoring information primarily for the implementing partner to report to USAID or the Mission to report to other internal or external stakeholders. Ideally, performance monitoring information is used far beyond reporting to inform programmatic decisions and actions, thereby continuously improving our programs (adaptive management in action!). If you are trying to reach that ideal, here are our six good practices for using performance monitoring information to manage programs more adaptively.

1. Monitor what you need to know to determine if you are (a) on track and (b) causing unintended outcomes.

One of the main problems we see in using performance monitoring information effectively is that the program is not tracking meaningful outcomes and is focused almost entirely on outputs. Outcomes are significant changes in the “conditions of people, systems, or institutions that indicate progress or lack of progress” (USAID ADS 201). Outputs, on the other hand, count things; the number of people trained is a common example. Tracking outputs but not outcomes means we cannot determine if the local system was substantially changed as a result of the program. Did those individuals who were trained change their behaviors or how their institutions function (short-term outcomes)? Did those changes lead to further changes (long-term outcomes) in health (reduced incidence of disease), education (increased graduation rates), etc.? These types of changes are outcomes. Not knowing if these outcomes are achieved severely limits our ability to manage adaptively – we’re not even sure if we’re having a negative or positive impact on the development challenge.

Another common pitfall is not monitoring unintended outcomes. Sometimes (maybe even a lot of times!) programs have unintended effects. One example I always share is a program I worked on in Liberia that was a community peacebuilding program. Through the process of empowering women in the community to lead community peace councils, we (unintentionally) emasculated men, leading to a negative outcome of an increase in domestic violence among the female program participants. This information came out through regular contact with program participants and qualitative interviews. If you don’t have ways to pick up on things like that, you can’t manage adaptively and mitigate those negative outcomes.

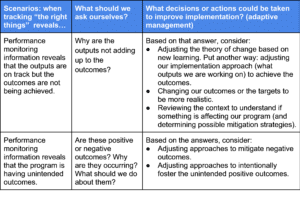

See the table below for how monitoring the “right things” can help programs manage adaptively.

2. Use the right methods to collect performance monitoring information.

Because performance monitoring is almost always assumed to be quantitative in nature, this good practice focuses on expanding the realm of possibility to include qualitative methods. One of the main deficiencies I observe in performance monitoring is the lack of qualitative methods. In the Liberia example above, if we only relied on quantitative, indicator-based performance monitoring, we would never have known about the unintended, negative outcomes.

I think it is always wise to incorporate qualitative methods because qualitative information provides nuance and context to the quantitative data you are tracking. It is also helpful for uncovering unintended outcomes. In those cases, we need the flexibility to uncover what we are not even sure we’re looking for, and qualitative methods can be more useful in doing that. Most Significant Change, outcome mapping and harvesting, etc. can be useful approaches here.

I’ll leave this good practice with the idea that it’s never “either/or” (quantitative vs. qualitative) but a “yes, and” so that methods are seen as complementary and get you the information you need to make informed decisions.

3. Manage, synthesize, and visualize the relevant information you collect to make it easier to use.

When we are working with USAID staff, we observe that the problem is often too much information rather than too little. In a way, this is a better problem to have, but it requires an approach that (1) determines what of this knowledge is important and useful (2) and synthesizes and visualizes that for users so they can efficiently make sense of it.

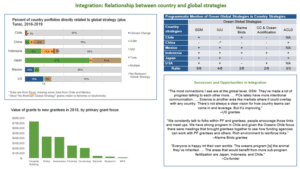

One method we have used in the past is called a data placemat, which is a not-so-fancy term for a one- to two-pager with all the critical pieces of information that you want users to grapple with. This includes both quantitative and qualitative data points. The placemat can be something that those attending a meeting review together and discuss (see practice 4 below). This synthesis with thoughtful data visualizations makes it digestible and easier for stakeholders to discuss what they’re seeing.

As part of quarterly reporting, a data placemat might be something that USAID award managers request implementing partners to submit. It can be the basis of a quarterly check-in on progress.

Importantly, before you create such resources it is important to speak with decision-makers: what questions do they have of the information? What answers do they need to inform decisions and actions on the program? This helps you focus your synthesis on what is most important.

Sample data placemat from Social Impact, Inc. (see another public data placemat here)

4. Ask critical questions of the synthesized information.

If we stop at synthesis, we haven’t gotten to actual data use. We must ask ourselves critical questions about the information that leads us to take the decisions and actions necessary to improve programming.

This critical thinking exercise can be done simply in a team meeting or in a larger pause & reflect session. It is important to consider:

- Who should be there? It is important to have decision-makers and those affected by decisions present.

- What is the right time for this conversation so we can use it to inform decisions and take actions? If we are looking at performance monitoring data from an entire year, for example, this is best done before work planning to inform any changes to the upcoming work plan.

- How do we set a learning tone in this discussion? It is about improvement, not blaming (individual performance challenges should be dealt with one-on-one).

I recommend this become a regular practice (quarterly, semiannually, or annually) so that it doesn’t only happen when we think things are “off course” but is just part of how we manage programs. It can be helpful to align this reflection with existing reporting schedules from the implementing partner to USAID to avoid extra data analysis burdens.

When teams and stakeholders sit to discuss the information, some questions to consider include:

- Are we on track to achieve the outcomes we anticipated? If it doesn’t look like we are, what may be contributing to this? Is something incorrect in our theory of change?

- Are we causing any unintended outcomes? Are those positive or negative outcomes? Why are they occurring? What should we do to address / mitigate the negative outcomes? What is causing the positive unintended outcomes and can we be intentional about making more of that happen?

Note that if the information you have access to does not help you answer these questions, then return to the first good practice above; in that case, your monitoring approach is likely insufficient to support adaptive management.

5. Decide how to manage adaptively and follow through.

Always end these conversations with discussing the implications of the reflection. What should we do now? How can we improve? What needs further exploration? Have clear decision points and persons responsible. Check back in on those the next time you’re meeting to make sure there is accountability to follow through.

The biggest mistake we can make is adhering to good practices 1-4 only to botch this good practice. Your team will lose interest in collecting and synthesizing useful information or participating in critical conversations if they do not see it leading to any improvements in implementation.

6. Document when and why you adapted.

Now you have clear decisions and persons responsible for carrying out those decisions. Well done!! The last good practice is to simply not forget to document these decisions, including what changes you made and why. We often forget what we ate for lunch yesterday; it is also easy to forget why we made critical, strategic shifts. Documenting your key programmatic adjustments in something like a simple pivot log means we don’t have to wonder a year later: “why did we do that again?” This helps avoid institutional memory problems and can help explain changes to new stakeholders and incoming staff.

We hope these good practices help you and your teams use their performance monitoring data more effectively!

Cover Photo Credit: Fauxel, Pexels

[1] Here is the full definition of performance monitoring from USAID’s Monitoring Toolkit. ADS 201 defines performance monitoring as “the ongoing and systematic collection of performance indicator data and other quantitative or qualitative information to reveal whether implementation is on track and whether expected results are being achieved. Performance monitoring includes monitoring the quantity, quality, and timeliness of activity outputs within the control of USAID or its implementers, as well as the monitoring of project and strategic outcomes that are expected to result from the combination of these outputs and other factors. Performance monitoring continues throughout strategies, projects, and activities.”

[2] USAID’s ADS 201 defines adaptive management as “An intentional approach to making decisions and adjustments in response to new information and changes in the context.” See USAID’s discussion note on adaptive management here.